No blog about birdsong in music would be complete without some thoughts on the music of twentieth century French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908 – 1992). He was an extraordinarily prolific creator of music inspired by birds, and, let me warn you, it’s not for the faint-hearted. Personally, I love it, but it’s wild, dissonant stuff, consisting of musical transcriptions he made while listening to birds, and underpinned by a world of deep personal beliefs and convictions, using complex technical modes and compositional approaches. You won’t find many recognisable tunes to help guide you through, but, with a little help, there are plenty of recognisable birds to be heard.

Described in a fascinating page on the oliviermessiaen.com website [https://www.oliviermessiaen.org/birdsong], Robert Fallon takes five birds from Messiaen’s Oiseaux Exotiques (1956), and matches their musical imitations with the actual recordings of birds from which Messiaen made his transcriptions [1]. (Messiaen kept quiet about these recordings, perhaps preferring to have his audiences believe he always transcribed his bird songs in the wild).

In this article, I’m attempting something similar, but looking specifically at Messiaen’s Reveil des Oiseaux (1953), a piece for piano and orchestra in which 38 different European birds appear across over twenty minutes of non-stop birdsong. I’ve also chosen five birds but, as there is no equivalent set of recordings, can’t make any direct comparisons. Instead, I’m attempting to match them up with birdsongs to be found on the inimitable xeno-canto website. Obviously these aren’t the exact birds that Messiaen would have heard and transcribed. But by audtioning and choosing birdsongs only from France, I’m hoping that we can hear something close to what Messiaen might have heard when he made his transcriptions around 7 decades ago. Who knows, maybe we are even hearing an actual descendent of a bird Messian heard?!

Bird 1: Chouette cheveche – Little owl

The first bird is the Little owl. Here’s what Messiaen has notated:

{Figure 3 in the score, solo violin)

‘Miaulement feroce’ translates as ‘ferocious meowing’.

I’ve created that moment for the violin:

[You can also hear it played by solo violin at at 3 minutes 9 seconds in this youtube recording: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FksGMUtrb38#t=3m9s]

In the performance I listened to (youtube link above), it seemed the violin player emphasised the first note of each set of three notes, but this xeno-canto recording of a Little owl would suggest an emphasis on the second (upper) note would be more authentic, with the first note much quieter (almost inaudible).

Xeno-canto XC883227

If I’ve chosen something close to the call Messiaen would haveheard, perhaps this rendition (with accents on the second note of each set of three) is a more authentic way to perform the Little owl?

Bird 2: Bouscarle – Cetti’s warbler

(Messiaen’s notation, the seventh bar after Figure 3, Eb clarinet.)

Played by the Eb clarinet (smaller than a normal clarinet). [Also heard at 3 minutes and 24 seconds on the youtube recording.]

But here is a recording of a (French) Cetti’s warbler:

Xeno-canto XC963920

Pretty close, I’d say! However, Messiaen’s notation asks the Eb clarinet player to play full crotchets for the first and third notes. I wonder whether making these notes shorter and detached (not sustained) would have sounded more authentic, like this:

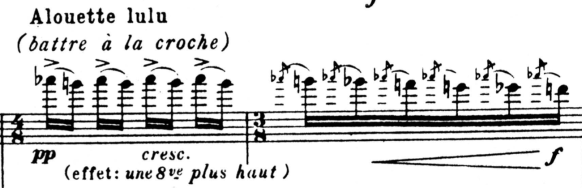

Bird 3: Alouette lulu – Woodlark

(The 10th bar after Figure 3, piccolo)

As heard on piccolo:

And a (French) Woodlark:

Xeno-canto XC906748

This one seems pretty good to me! Perhaps inviting the player to slightly speed up during the second bar would have increased realism a little, but I’m definitely hearing it. (Heard at 3 minutes and 30 seconds on the youtube recording.)

Bird 4: Pouillot veloce – Chiffchaff

(2nd bar of Figure 4, xylophone)

Played on xylophone:

And sounding like this:

Xeno-canto XC991171

By the time we reach this bird in the score, there is also a Blackbird singing (on celesta) and a Litle owl call (on solo violin) so it’s slightly hard to pick out of the mix (as are birds in true life). There are obviously features that are very Chiffchaff-like, such as the repeating note alternating between slightly different pitches. But perhaps Messiaen’s birds were slower than this modern one, because I certainly couldn’t find one this slow. (Heard at 3 minutes and 46 seconds on the youtube recording.)

Bird 5: Pic epeiche – Great spotted woodpecker

(6th bar of Figure 7, woodblocks -‘even and fast – on rubber sticks)

‘Tambourinage du pic epeiche’ translates as ‘the drumming of the great spotted woodpecker’

(Heard at 5 minutes and 02 seconds on the youtube recording.)

Here it is played on wood blocks:

I don’t want to insult your intelligence by giving you this example from xeno-canto, but here it is anyway, just for fun:

Xeno-canto XC961468

In the preface to Reveil des Oiseaux, Messiaen stated: “This score contains only birdsong. All were heard in the forest and are perfectly authentic.” He asks that the instrumentalists to “try to reproduce, as much as possible, the attacks and timbres of the birds” (which are named in the score) giving onomatopoeic words to assist them in this. He even recommends that the pianist goes for forest walks to become familiar with the specific birds they will be playing!

As far as being ‘perfectly authentic’ goes, writers disagree on the extent to which this is true. Robert Fallon (2007) points out that Messiaen had to write musical parts that were actually playable by human performers, and, after making detailed comparisons between the musical transcriptions in Oiseaux Exotiques and spectograms of the recordings of the actual birds he imitated, Fallon estimates Messiaen achieved fidelity to his model two thirds of the time [2].

Paul Griffiths (1985) described Messiaen as a “far more conscientious an ornithologist than any earlier musician, and far more musical an observer than any other ornithologist” (p.168) [3]. The fact that ornithologists listening to his birdsong music mostly failed to recognise the birds from the music was a source of disappointment to Messiaen [3]. I confess I also failed to recognise most of the birds in Reveil des Oiseaux when I first listened with the score (in French) and before knowing the Englsih translations of certain birds. But once I knew which bird was being portrayed, I often found myself recognising its distinctive qualities (such as the repeating phrases of the song thrush, the alternating pitches of the chiffchaff, the falling interval of the cuckoo).

By beginning with the music of these five distinctive birdsongs, and then listening intently to birdsong audio to search for something similar to what Messiaen may have heard, I find myself starting to hear birds differently, maybe even with something more like Messiaen’s musical ears!

- The recordings Messiaen used for Oiseaux Exotiques were six commercially produced 78 rpm records published in 1942 as American Bird Songs by Comstock Publishing, which he played on his own record player.

- Robert Fallon: The Record of Realism in Messiaen’s Bird Style in OLIVIER MESSIAEN: Music, Art and Literature. ed. Christopher Dingle & Nigel Simeone (Ashgate, 2007).

- Paul Griffiths: Olivier Messiaen and the music of time, Chapter 10 ‘Birdsong’. (Ithaka, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985).