As mentioned in part one, the music for Racer Snakes vs Iguanas falls into five sections, each section consisting of tension music followed by sudden action music. In part one, a hatchling emerged, was chased by racer snakes, but ultimately achieved safety on top of the rock by the sea.

The next four sections tell more stories. Starting with tension, (a low B drone at 22 mins 10), the scene is set for the next baby iguana to attempt the journey. But first, a tiny metallic sound cuts through the musical mix as we see a dead creature on the sand, leading us to feel horror at the thought of death by snakes. We are reminded that, although the snakes missed their chance to capture the first hatchling, sometimes they are successful; the softer low string note that follows is warmer and more expressive as our eye is drawn to the next iguana, suggesting a sense of compassion for the baby that is facing such a harsh life.

For a group of snakes waiting, motionless but alert (22 mins 25), the B bass note drops away and a strange, faint alternating pair of tones cuts through, like a very distant siren; an alarm. It gives a sense of being suspended in mid air, as if we are holding our breath. More associations follow: the music now has a passing resemblance to the John Williams’s score for the famous snakes scene in ‘Indiana Jones’: both feature faint rattling sounds (perhaps suggesting rattle snakes?), notes sliding upwards in pitch, atonality (no steady tonality), and no pulse. The sound of instruments sliding upwards, traditionally a glissando on violins, is the stuff of cinematic horror. We all associate this with previously heard tension soundtracks, but may also recognise in the music, perhaps subliminally, what growing panic feels like: as our body physically prepares for attack, with adrenaline causing our hairs to stand up on end (like the upwards pitch bend) and the sense of insecurity (no tonality) and time slowing down (no pulse).

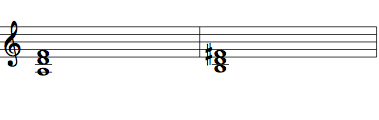

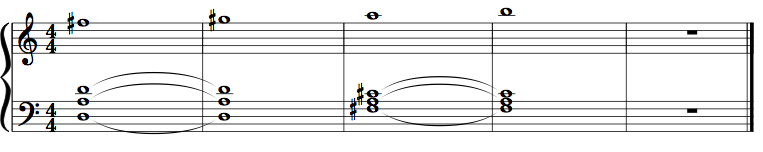

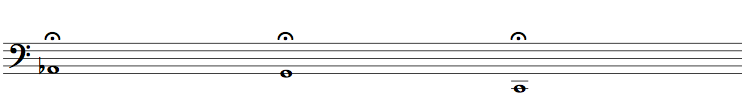

As the hatchling pauses to look round and a snake immediately freezes, the music also pauses. The music is inviting us to become emotionally invested in every movement, every tense wait, and every sudden spring into action. This time, the action music has a tonality (before it was just percussive), firmly established in Ab minor (or G# minor…I haven’t seen the notation!).

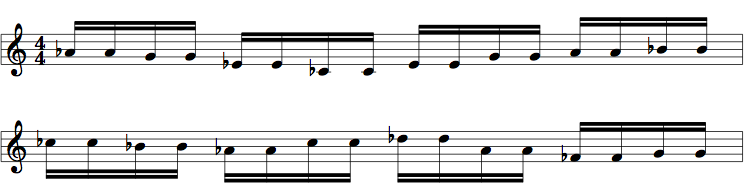

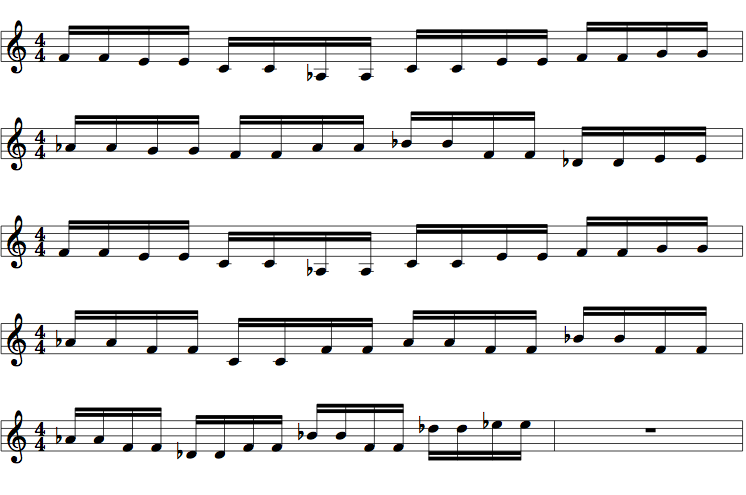

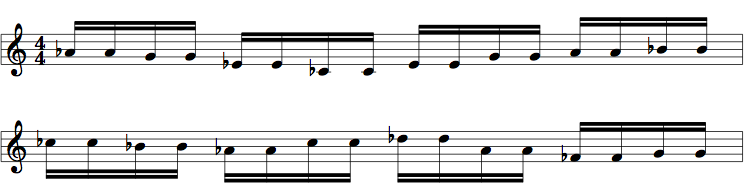

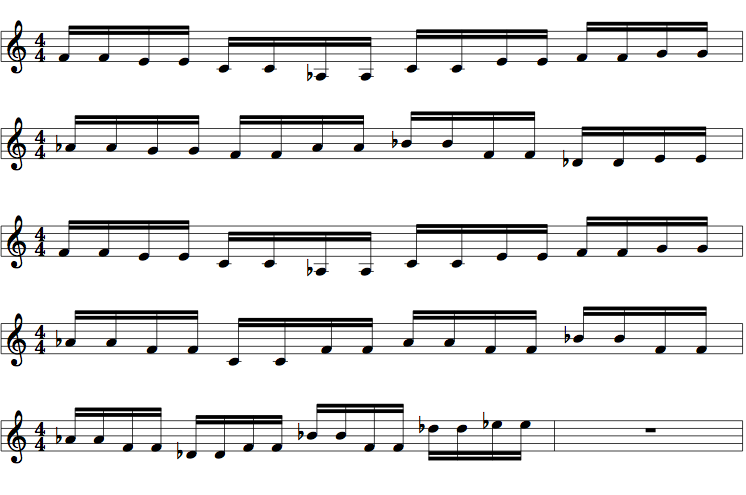

Here are the conventions of cinematic action music; over pounding percussion, a tune in a strongly minor tonality (Ab minor) is played in fast pairs of notes played by violins and violas using a bowing technique called spiccato (in which the high-speed bow appears to bounce off the string).

Erupting from silence, the effect is one of heightened excitement and energy. This hatchling reaches the rocks, but the music informs us it is still in danger. The pounding music momentarily changes to tremolando string notes (where the bow moves backwards and forwards incredibly fast) producing a sound reminiscent of the physical sensation of trembling. The bass note is a D, a tritone away from the Ab tonality, a pairing of notes that are the least stable tonally. This time the iguana is caught by snakes, but instead of pausing with tense music, the action music resumes, another hatchling races forward, is caught, and then another tries. As the music presses onwards through each of these captures, we feel the breathless pace of these attempts, edited to occur one after another. We sense that maybe even the camera operator was surprised by the second capture, having visually tracked further to the left after the attack happened.

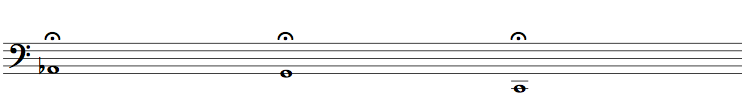

It’s when the next iguana is caught that the music draws back onto a new drone, on Eb, (23 mins 18) with a single deep ‘thump’ similar to those we often hear in movie trailers. This is the feeling of our heart ‘missing a beat’. When the bass lowers to a C for an extended stretch of tension music (the third section), there is a brassy edge to the note, suggestive of the ‘Braaam’ sound which, since the film ‘Inception‘, has become the ubiquitous sound of the Hollywood dystopian nightmare. This tension section is longer than the others and has a stillness to the low note, and little narration. We, the audience, now know what might happen. We have been invited to watch the images of murderous writhing snakes through the eyes of an emerging hatchling. The wait heightens the tension further (although I notice the music in the TV album soundtrack is cut by approximately 14 seconds at this point).

For the next chase, the action music is now in F minor (23 mins 59), lower than before. As the iguana fails to make it to the rocks, the music also fails to resolve from a rising phrase (24 mins 09). The final F is missing, but slowly emerges as another held drone note.

The tension/waiting sequence that follows features an extraordinary shot of five snakes simultaneously straining forward (24 mins 12). The musical drone that marks this moment includes an almost ‘slurping sound’ mixed in (suggesting death by squashing?), as well as a menacing gong with a long reverb, and the beginning of a slow bass note descent from Ab to G to C. The effect is dark and full of foreboding. Anyone who is a fan of Rachmaninoff will recognise in these notes (when transposed up a semitone) the long slow opening of the C# minor Prelude, with a similar feeling of darkness and creeping danger. A stillness comes over this bass note, C. The iguana must hold its nerve keeping still.

The effect is dark and full of foreboding. Anyone who is a fan of Rachmaninoff will recognise in these notes (when transposed up a semitone) the long slow opening of the C# minor Prelude, with a similar feeling of darkness and creeping danger. A stillness comes over this bass note, C. The iguana must hold its nerve keeping still.

A crescendo leads into, not action music, but a moment of silence, as it breaks into a run (we hear just the sound of its feet on the gravel). These touches of withholding hearing what we’re expecting keep our attention finely tuned for any eventuality – there is not a predictable moment in the whole sequence. Instead of action music, three slow strikes on the drum, as new snakes slither out of a hole in the rock, like the sounding of a death toll. Again, the sound of horror: string sounds sliding upwards, a brassy sound sinking downwards in pitch. Here, we are invited not to feel the exhilaration of a chase, but a horror of the pursuers. (The iguana now appears to be being chased by eight snakes.) Director Liz White describes how the music for the whole iguana/snake sequence was the one the composers ‘really, really had to work on to get it just right’, and that they did a fantastic job of getting ‘the right amount of tension’. [1]

When the music finally reverts to the chase action theme, it is now in F# minor, a semitone higher than before, subliminally giving it a feel of increased energy. Just as the iguana’s run is interrupted by a sudden capture, so the action music is halted abruptly, and a tense D minor drone creeps in, with rising strings notes representing the snakes. However, this morphs into D major, a more hopeful-sounding tonality, as the iguana, amazingly, escapes their grip.

It is in the fifth and final action sequence that the truly epic nature of this cinematic music is revealed. I would like to describe its story-telling power in part 3.

F# minor Eb (or D#) major F# major F# minor

F# minor Eb (or D#) major F# major F# minor D major F# minor

D major F# minor

The effect is dark and full of foreboding. Anyone who is a fan of Rachmaninoff will recognise in these notes (when transposed up a semitone) the long slow opening of the C# minor Prelude, with a similar feeling of darkness and creeping danger. A stillness comes over this bass note, C. The iguana must hold its nerve keeping still.

The effect is dark and full of foreboding. Anyone who is a fan of Rachmaninoff will recognise in these notes (when transposed up a semitone) the long slow opening of the C# minor Prelude, with a similar feeling of darkness and creeping danger. A stillness comes over this bass note, C. The iguana must hold its nerve keeping still.